Revealed! How Jeremy Corbyn is wiping out humanity! An essay

12August 14, 2015 by Harnessing Chaos

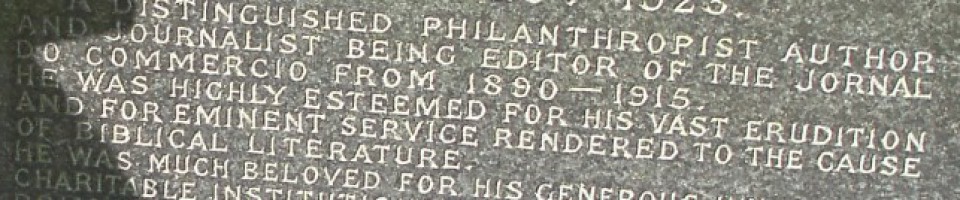

‘Comment is free, but facts are sacred’—C.P. Scott, former editor of the Manchester Guardian

The propaganda model developed by Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman suggests that media discussions of politics and foreign policy broadly reflect elite discourses and corporate interests, irrespective of whether elite opinions are in agreement over details or not. Individual journalists may think differently and sometimes may publish differently. But, broadly speaking, media outlets will foreground issues which help manufacture consent and certain agreed assumptions of debate.

The Guardian has a reputation for being a left-wing newspaper. Certainly there are columnists who are quite openly so and/or who set themselves against the economic consensus established by Thatcher and then Blair e.g. Owen Jones, Dawn Foster, Seumas Milne, George Monbiot, and Zoe Williams. But in broad terms the Guardian is still overwhelmingly accepting of this economic consensus in its overall emphasis, editorials and, as we will see, often unspoken assumptions. Advertising plays a significant role in its income and the Guardian is owned by the Scott Trust Limited. In other words, and to state the obvious, the Guardian is part of the corporate world just like any other mainstream media outlet.

What is notable is that the Guardian can sell radicalism to its reader, plenty of whom (if letters and comments are anything to go by) are more critical of the Thatcher-Blair economic consensus than many (most?) Guardian writers. For instance, any regular visitor to the website will have noticed this advertisement, including, as some have noted, on anti-Corbyn articles:

In normal circumstances it is relatively easy for the Guardian to keep more radical readers relatively happy with qualifying statements about having to hold your nose and vote for Labour over Tories, or even in articles critical of neoliberalism, though the signs were there of a more controversial centrist direction when they suggested voting Lib Dem in 2010.

But circumstances have just changed and are exposing the limits of what the leftish end of the media can accept. The emergence of widespread support for Corbyn among Labour supporters has, probably more than anything else, revealed how the Guardian is involved in the manufacturing of consent. Corbyn’s policy suggestions could even be classified as a Keynesian critique of the current Thatcher-Blair economic consensus which would only further highlight how narrow and far to the economic right the current consensus now is. So how has the Guardian reacted? Despite individual articles of support, there were, for a start, over 20 anti-Corbyn articles in one week, though the Guardian has now had to relent a little after a reader backlash (they’re still punters, after all). But a steady narrative has remained, despite the occasional pro-Corbyn article. The narrative includes key elements which have claims like Corbyn being a throwback to the 1980s and completely unelectable, just like Michael Foot was unelectable in 1983, and that this unexpected phenomenon is probably just due to a bunch of starry-eyed young people. Sometimes it is just obviously the fault of the other three candidates for being boring or the like, with the assumption that no one (or no one sensible and mature) could actually believe the kind of things Corbyn espouses. This basic narrative has been colourfully expanded in the Guardian and among Labour MPs. Here are just some of the highlights:

- Michael White, July 30: implicitly compares Corbyn’s followers to the ‘popularist fundamentalism’ of ISIS (ISIS, we recall, are popularly known for decapitating and burning people)

- Jonathan Jones, August 8: loosely suggests Corbyn’s ideas and following are haunted by Stalin and co, and even mentions mass murders. Even terms such as ‘the 1%’ (developed by, for instance, the anarchist David Graeber and the economist Joseph Stiglitz) and ‘austerity’ (used across the political spectrum) are deemed ‘neo-Marxist’

- Suzanne Moore, August 12: claims to represent a socialist tradition that is the opposite to Corbyn’s ‘asceticism’ and Corbynism represents a ‘kind of purity’ which ‘always shades into puritanism, an unbecoming exercise in self-flagellation’ (‘So you have your Bennite tea, I shall continue to demand the finest wines known to humanity’)

- Rowena Mason, August 13: ‘Jewish Chronicle accuses Corbyn of associating with Holocaust deniers’

So what do we do with all this? On the potentially puritanical reign of Corbyn, Moore is presumably making some strange assumptions about the readership of the Guardian, many of whom appear to be pro-Corbyn. Presumably the advertisers advertising luxury villas and expensive holidays regularly in the Guardian will need to find a different audience if Moore is right…? Moore’s argument, lacking in any relevant supportive evidence, was further supported by Polly Toynbee on Twitter, who has been regularly critical of the right-wing dominance in the British media and of the media treatment of Ed Miliband:

Moore, who unlike most people, has a regular platform in the Guardian to air her views, wondered what might be next:

https://twitter.com/suzanne_moore/status/631776210641649664

Moore is not the only person in elite circles who fears a Corbynite banning (for which there is no evidence), but what all of these sorts of interventions have in common is that they are fears invented by the journalists. The Guardian presumably has no editorial worries about some obvious inaccuracies. So let us state the obvious. There are no obvious parallels (loose or otherwise) between Corbyn followers and ISIS, though, from the perspective of a journalist like Michael White, anything challenging the Thatcher-Blair consensus (e.g. nationalisation of railways, non-renewal of Trident) must by definition be constructed as ‘fundamentalism’. Jones’ youthful toying with Soviet Russia in the 1980s has no obvious connection with people not discussing Soviet Russia today. Besides, it was the events of 1956 which led to the haemorrhaging of support for the Communist Party and its Soviet connections, so Jones may have to ask himself why he got so caught up in this in the 1980s. What is notable is that the only person I am aware of in the media debates surrounding Corbyn who has had sympathies with Soviet Russia is Jonathan Jones. What is also curious is that Guardian writers are implying (presumably unintentionally?) that much of the Guardian readership, and some of its published articles, must be implicitly supportive of the Soviet Union, totalitarianism, and ISIS, a most peculiar assumption for a newspaper that prides itself on its liberal heritage.

In the case of Corbyn’s alleged dubious associations, the article did publish a number of points already made by Corbyn where he responds that the allegations are false. Fair enough, it would seem. But, as most of this response was already known to the Guardian, it is striking that the allegation was placed towards the top of its website with the headline: ‘Jewish Chronicle accuses Corbyn of associating with Holocaust deniers’. The fear can remain while simultaneously maintaining ‘balance’. (This continues).

Indeed, such allegations were discussed extensively on Twitter, typically with no mention of Corbyn’s response. Toynbee endorsed another anti-Corbyn Guardian article (‘Why is no one asking about Jeremy Corbyn’s worrying connections?’) about his alleged dubious connections:

The article by James Bloodworth also has this among its closing words: ‘So why are Corbyn’s fellow leadership contenders so unwilling to challenge him on any of this?… Much of this demonstrates, as I mentioned already, that a politician can at present take almost any position on foreign affairs and get away with it.’

For the sake of argument, let’s assume the worst case scenario: Corbyn really does have dubious associations and would take us down a dark alley. We still might indeed wonder why Corbyn’s alleged associates and foreign policy has not been discussed in detail with reference to the other candidates, or indeed by the other candidates. One reason for this might involve Tony Blair and Iraq. Two candidates (Burnham and Cooper) voted in favour of the invasion of Iraq. Kendall wasn’t in parliament at the time of the Iraq war but is the candidate most closely associated with the Blairites. Iraq is (now) something a number of Labour MPs dearly wish they were not associated with and has cost the party a huge amount of votes since 2003. In addition to Iraq, association with Blair might not be helpful in discussion of foreign policy and dubious associations, including his support for dictators such as Karimov (who appears to have boiled opponents), Gaddafi, and Mubarak, or we might even point to Tony Blair Associates’ work with Nazarbayev. Interestingly, the Guardian have yet (as far as I am aware) to run detailed articles in this leadership campaign on the connections of Burnham, Kendall, and Cooper with Blairite foreign policy. Toynbee knows about such connections but, significantly, only keeps the focus on Corbyn. So is Bloodworth right? Can politicians really get away with a range of positions on foreign affairs? Why not test it out on The Other Three too? Or will we find that the answer is murkier than we want?

Even the seeming ‘common sense’ of the standard narrative of who can and cannot get voted in is crucially lacking in complexity. For a start, the 1980s is not the 2010s and 2020s and vice versa. There are no convenient laws to say because x happened in 1983 it will therefore happen again in a different historical and political context. A very recent example which has got a fair amount of press coverage has come from Robert Webb of Peep Show fame. He tweeted the following (among others):

https://twitter.com/arobertwebb/status/631886999482449920

https://twitter.com/arobertwebb/status/631887255947345921

https://twitter.com/arobertwebb/status/631887402408247296

Guido Fawkes claimed, ‘It’s a better argument against Corbyn than any of the actual candidates have managed so far…’. I’m not sure that this is an entirely accurate assessment as The Other Three (Burnham to a lesser degree) have made similar claims (as have plenty of others), though note the assumption that Corbyn’s popularity is boiled down to the failure of The Other Three.

So let us turn to Webb’s much-discussed arguments. We might note that it was Kinnock, who has come out strongly against Corbyn in the Guardian, who was leader of the Labour Party from 1983-92. But presumably it wasn’t his fault according to Webb’s logic. Instead it’s the ‘Bennites’ who fucked Labour. This too is curious because Benn’s influence in the Labour Party was clearly on the wane in the 1980s. He may narrowly have missed out (yet still missed out) on Deputy Leader in 1981 but by 1988 Benn’s campaign for the Labour party leadership (with ‘Bennite’ Eric Heffer for deputy) failed by an overwhelming margin. With Benn now firmly marginalised, Kinnock was now emboldened and would, of course, still go on to lose in 1992.

Can we not blame the 1983 election on ‘the Bennites’? We could point out that Benn and the then Labour leader Michael Foot did not see eye-to-eye but, even so, Labour stood on its most leftist platform over the past 40 years and lost. However, there were a number of factors at play which are not particularly controversial (analytically speaking). Thatcher got a significant electoral boost from the Falklands War and Labour suffered electorally from figures on the right of the party leaving to set up the SDP. This is certainly not to say that there would have been a Foot government in 1983 had it not been for the Falklands and the SDP split, or that the SDP split is somehow unrelated to leftist views on the Labour frontbench. However, this was one election from over 30 years ago with its own particularities. We might ask why Kinnock is not being blamed for defeats in 1987 and 1992 but Kinnock is part of the consensus and the Labour establishment so a more crude blame game is being played: it’s the fault of the increasingly uninfluential (on front bench politics) ‘Bennites’ which means, so the implied logic goes, that the ‘Corbynites’ would have the same result.

Finally, we might turn to nationalisation which is quintessentially (bad) 1970s and 1980s in such thought, certainly in some of the Guardian reporting. What is not often recalled in the criticisms of Corbyn is what he actually said, which I flag up for point of contrast with some of the criticisms (though not necessarily Webb’s):

I believe in public ownership, but I have never favoured the remote nationalised model that prevailed in the post-war era. Like a majority of the population and a majority of even Tory voters, I want the railways back in public ownership. But public control should mean just that, not simply state control: so we should have passengers, rail workers and government too, co-operatively running the railways to ensure they are run in our interests and not for private profit.

In sum, all detail and complexity of history is masked over in the manufacturing of consent in favour of a narrative assumed to be true. It is pretty clear that people like Webb and Toynbee are claiming to be pragmatists and, especially in the case of Toynbee, would like to be more radical in an ideal world. But intentions should only play a secondary role here. It remains clear that Corbyn is functioning in a way which challenges the assumptions of the mainstream media and journalists (irrespective of personal intentions) in a way that selling a radical t-shirt or a few articles on the evils of neoliberalism does not. Now it matters. But what is notable, however, is that it does not yet seem to be working. If anything, it seems to have galvanised support for Corbyn. One reason for this is that plenty of Corbyn supporters will be more familiar with these sorts of details than those with less interest in the Labour movement. But I do not think this is the end of the power of the propaganda model. If Corbyn wins the leadership election, everything will be thrown at him, and how this shapes the debate beyond the Labour movement will no doubt be different from the debates in the Guardian, comments sections and on Twitter. And, of course, this has already begun in the right-wing media. Indeed, the Daily Mail has even managed to outdo the Guardian: ‘Revealed: How Jeremy Corbyn welcomed the prospect of an asteroid “wiping out” humanity’

PS after some fairly wild misrepresentation on Twitter, let me clarify some points:

- This analysis works at the level of media discourse. What does the media emphasise and not emphasise and why?

- This does not mean Corbyn should be left unscrutinised by the media. The question raised by Bloodworth was why foreign policy is not being fully investigated in the election. It’s a good question and I think there is good reason: it probably would not look good on any of the candidates.

- There are better venues for analysis than Twitter.

- I don’t, er, support Hamas. Not that I thought that I’d ever have to defend myself against such an allegation, but it really, really, really isn’t my kind of thing.

- For what it is worth, it does not necessarily follow from this sort of analysis that Corbyn is right on Hamas. Assessing Corbyn on Hamas is not the point of the above article. My personal agreements and disagreements with Corbyn’s views is another question. The point of the article was to discuss his function in the contemporary media, especially the Guardian.

- Not that it was relevant for the above article but given that people were happy to throw around allegations (including ‘apologist for an anti-Semite’–really, Corbyn is an ‘anti-Semite’? Come on!) just because I said that to explain the emergence of Hamas partly as proponents of social justice in the sense that they supplied food and services and were perceived by Palestinians to be an improvement on Fatah is not to say that this is my view of social justice, that I agree with Hamas, or anything of the sort. To say that Hamas carried out such deeds and that their deeds might be described as ‘social justice’ while simultaneously killing people is a perfectly normal explanation. To explain the rise of Hamas is not to justify the rise of Hamas. This is not (to repeat yet again) to deny that Hamas do terrible things. In fact, I agree with (and what I meant on Twitter was something like) what the Guardian leader had to say on the election of Hamas in 2006: Hamas is no ordinary political party. Until it participated in this election it was best known in Israel and abroad for the suicide attacks it used against its Israeli enemies. In Gaza and the West Bank it was admired for its network of social services and opposition to the corruption which became a byword for Fatah and the PLO, under Yasser Arafat and then Mahmoud Abbas. Ideologically, Hamas is close to where the PLO was 30 years ago, wedded to armed struggle and to the replacement of Israel by a Palestinian state. It was hardly a good sign when its leader in exile met recently with the Iranian president, who calls for the eradication of Israel.

- Now do you believe that the Propaganda Model is right…?

I wish I knew the ‘backstory’ of all this.

LikeLike

Well, it begins just over 100 years ago…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very good piece. Much of the Pollyesque hatred of Corbyn’s campaign is that he threatens the self appointed position and ego of public arbiters. If the world is to be “changed”, and always at the margins, then it will by them, certainly not by any unwashed mass.

I am old enough to remember Toynbee’s virulent fear and loathing of organised labour in the 70s and 80s. It was that as much as ‘Europe’ that wedded her to the SDP, a topic still toxic for her. Martin Kettle has the legacy of his father’s CP days to haunt and taunt him, to the point of open absurdity. Patrick Wintour’s role as an upmarket sewer pipe for (any) power is unchanging. Its his life work.

The elitism of a dying Fabian socialism runs deep through it all. WE do the decisions, we manage, we police, you defer, and keep your fkg noses in the feedbag… or else. Well, no longer Comrade.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Richard. One of the curious things about the allegations turning on the 1970s an 1980s is that in the case of, for instance, Toynbee and Kettle (and let’s not forget Jones) is that they are replaying or dealing with the past as much as anyone (as you imply). what will also be interesting is to see how Kettle, Toynbee et al react if Corbyn wins. Will there be anything significant in the way of mainstream media support other than the odd Guardian columnist?

LikeLike

Reblogged this on TheCritique Archives and commented:

Fine sum up of how right-wing-Blairite the Guardian really has become, and how heavily this orientation has skewed its coverage of Jeremy Corbyn’s bid to become Labour leader.

c/o Professor James Crossley.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on markcatlin3695's Blog.

LikeLike

This is brilliant. Moore’s piece was the most empty. That Jeremy’s pleasures do not come from spending lots of money is not the point of his politics which is about getting rid of poverty not pleasure. The limits of acceptable discourse can include a claimed emotional attachment to peace and fairness as an ideal but not the acceptability of actually organising to achieve them – so Toynbee split from Foot’s party to join the SPD of the pro missile David Owen. She says that in her heart she is perhaps even more left wing than Corbyn. Hmm.

People have been scratching their heads over the apparent contradiction between one poll in which a big majority of every sort of person say they would be more likely to vote Labour if Jeremy leads it, and another in which the majority say a Labour party under Corbyn is less likely to be voted in. There is no contradiction here. The first poll asks people to relate to their own experience, the second to the consensus. (Minor point: Jeremy does not support Hamas, he supports democracy, an end to the siege and occupation).

LikeLiked by 2 people

Many thanks for these points and you put the criticism of Moore better than I did. I also agree that once peace and fairness are organised and potentially going to be achieved then then the reaction is serious. I’d only add that on the Hamas I was tired and having to defend myself on Twitter for what was a standard view of their rise to power in 2006 (food supplies, disillusionment with Fatah etc). It does say something about manufacturing consent when, defending an article such as this one, I had to spend far too much time explaining I wasn’t a fan of Hamas (!!!) and if I’m getting this, I can only imagine the level of attacks Corbyn is going to face.

LikeLike

Well, I’d guess that Toynbee, Kettle, the increasingly bizarre Michael White et al are now at or approaching the end of their careers. A new younger commentariat is emerging but so much has changed in how people consume and interact with media that I doubt they have the same influence. Certainly not the deference.

Owen Jones is so close to the Labour Party and its loyalties, that and the Guardian are his core enablers, that he will at crisis point move from advocating change to defending the Party as is – all in the name of “realism”. Then the backlash begins. An unusual experience for him.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, agreed.

LikeLike

Thanks for this piece James. It admirably and succinctly explains what is so wrong – and so disturbing – about the onslaught from so many in the labour heirarchy on Jeremy Corbyn. I think it’s backfiring at the moment as it only makes me, and I’m sure many others like me, to do all we can to ensure he gets elected. However I’m shocked at the lack of insight from so many allegedly intelligent commentators and public figures. I’ve recently finished Owen Jones book on the establishment and it’s alarming to see the labour party and so called left leaning journalists behaving in precisely the way Jones describes the establishment – it’s not left wing or right wing it’s defend the status quo at all costs.

I keep asking myself why I wish to support Corbyn – all the negative comments seem to miss the point – and I think Richard Harris above makes a very strong point about elitism and the fabian mentality. Whenever I watched a broadcast during the general election build up it seemed to be a pre-scripted affair between two people in suits both of whom had been driven to the studio in the back of a big car – I never once felt I was watching an ordinary person who maybe went there on the bus, talking to another ordinary person in the way we have conversations and discussions and arguments away from TV studios. Even Ed Milliband, who I liked, got caught up in it to an extent. Corbyn is unlike every single one of them. He is not elite, he is not better than us – or worse – he is a man who has been elected to serve a constituency and is doing so – and may be elected to run a party and will do so. He expresses his thoughts and ideas and he asks questions and he gets us to think and discuss – what more do we need?

Thanks for helping to explore this without bias James.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank-you. And yes, while there is clearly a desire for a different kind of politics, it is clear that Corbyn’s focus on issues minus the standard, safe political soundbites and even dress sense has an obvious appeal (and not that it is unconnected to a different kind of politics). As for your comments on elitism, Fabianism and the establishment, yes, and I think the shock among journalists (who initially saw Corbyn as an irrelevance) was part of this. As Richard Harris pointed out, this is shaking things up in the media world too and when it settles it won’t be the same, though we should not underestimate the ways power can be reasserted.

LikeLike