Corbyn: The New Puritan?

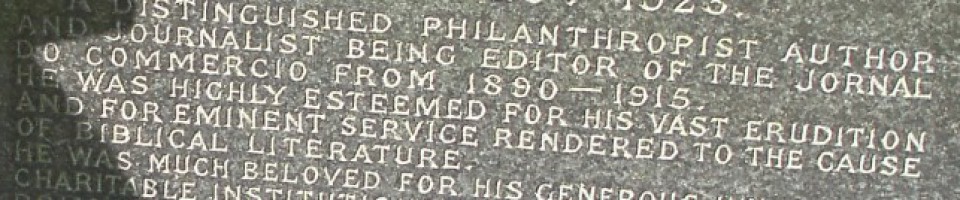

7July 15, 2016 by Harnessing Chaos

Sects and Broad Churches

Part of my interests in the history of modern English political discourses and constructions of what the Bible, Christianity and religion are deemed to be, has involved the use of the derogatory label of ‘sect’ and ‘cult’ to describe an unwelcome variant of a political movement. The main movement might typically be described more positively as a ‘broad church’ and authorities from its past (e.g. Atlee, Bevan, Bevin, Cripps etc.) are appropriated as part of the broad church rather than the sect which may also be laying claims to such figures. Historical order is brought upon any chaotic, contradictory, or potentially unwelcome behaviour of such figures while the present enemy is constructed as some sort of aberration. ‘Sect’ or ‘cult’, then, is something other people do. There have been plenty of examples of this since Corbyn became leader of the Labour Party last September, which I have discussed in more detail elsewhere. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, this has continued in the recent post-Brexit crises which have, of course, had their own particular impact on the Labour Party.

None of the examples that I have previously looked at had any real awareness of ‘sect’ or ‘cult’ as an analytical category in the study of religion. However, a recent related example has come from Gordon Lynch who is not only active in his local Labour Party but is also the Michael Ramsey Professor of Modern Theology at the University of Kent in what is, to my mind, one of the best religious studies departments around. Lynch’s official title might obscure his research interests in sociology and the study of the media. But experts too are collectable data. Rather than what appears to me to be the far more common labels of ‘sect’ and ‘cult’, Lynch opts for labels such as ‘puritan’, ‘evangelical’ and ‘conservative religious groups’ to define at least some aspects of the Corbyn movement (this is not, however, unprecedented) in his (The Fall-sounding) blog post on After Labour?, called ‘Corbyn and the New Political Puritans’.

Lynch’s New Puritans

Lynch’s suggestions were based partly on his experience of Corbyn supporters at his local Constituency Labour Party (CLP) meeting this past week. For such supporters, he claims, Corbyn ‘is the symbol and architect of the true socialist party for which they have yearned for so long’ and their support for him is ‘impervious to any critical reflection’. As a sociologist of religion, he points out that he has ‘never experienced an atmosphere like that Party meeting anywhere before outside of conservative religious groups’.

This Corbyn would have been banned by some Puritans

Such groups ‘are deeply convinced of the truth of their way of seeing the world’, ‘a movement of moral certainty, largely devoid of policy, fuelled by symbolic struggles against evil, treachery and compromise’. The growth of Party membership ‘was, as in any committed Evangelical group, taken as confirmation of the moral rectitude of the movement, with no interest shown in whether connections with the wider electorate were being made.’ Despite courteous exceptions, ‘the movement forming around him is, at its heart, a form of political puritanism’ with ‘the characteristics of a puritan movement’ and with Corbyn functioning as ‘a model puritan leader’. Even ‘[t]rying to fight with puritans’ will only re-energise ‘their sense of being engaged in a grand moral drama, struggling against forces of darkness within and beyond their movement’.

Whether Lynch is right or wrong about this specific case as an accurate sociological analysis, I leave partly to one side. His argument is, in fairness, a blog post reflecting on a meeting attended the previous day rather than an extended research piece. Furthermore, I have no access to the meeting at which he was present so I cannot challenge him on the reports of participants and nor can I realistically seek out the views of those Corbyn supporters present (not that I doubt Lynch’s reporting, I should add). Instead, I want to focus on how Lynch uses and constructs and controls political affiliations in relation to ideas relating to religion as data for my own gathering of uses of such language. In this respect, Lynch’s case is approximately that of those who have argued that the Hard Left is some kind of ‘sect’ in relation to what is understood to be a more reasonable centre of political discourse (in this case something like the views represented by the majority of the Parliamentary Labour Party). In this instance the notion of ‘puritan’ is obviously used to label those with disagreeable views of the sort that might be associated with Militant Tendency of the 1980s. But, irrespective of whether Lynch is proven right about the ‘heart’ of the movement around Corbyn, is it not a label that Corbyn supporters could reapply to one figure most prominently associated with the Right of the Labour Party, Tony Blair?

Indeed, when I read comments such as ‘deeply convinced of the truth of their way of seeing the world’, I immediately thought of Blair, particularly his attitude towards the Iraq war in the face of such vocal disagreement.  Blair even used ‘apocalyptic’ language in trying to convince the Labour Party to support the War on Terror. And did not New Labour (including Alastair Campbell, who has used the language of ‘cult’ to critique Corbyn’s followers) and its famous ‘on message’ approach, mean it too was, by the definitions of Lynch and others, ‘puritanical’ or a ‘cult’, sufficiently unwilling or unable to reach out to public opinion by the time of the 2010 Election? Was New Labour not ‘evangelical’ in counting numbers of voters and election victories ‘as confirmation of the moral rectitude of the movement’? In fact, Blair himself could use the sectarian constructions of others within New Labour who did not agree with him, including Gordon Brown and much of recent-ish Labour Party history. And note the contrast with Blair’s understanding of the Pauline moment:

Blair even used ‘apocalyptic’ language in trying to convince the Labour Party to support the War on Terror. And did not New Labour (including Alastair Campbell, who has used the language of ‘cult’ to critique Corbyn’s followers) and its famous ‘on message’ approach, mean it too was, by the definitions of Lynch and others, ‘puritanical’ or a ‘cult’, sufficiently unwilling or unable to reach out to public opinion by the time of the 2010 Election? Was New Labour not ‘evangelical’ in counting numbers of voters and election victories ‘as confirmation of the moral rectitude of the movement’? In fact, Blair himself could use the sectarian constructions of others within New Labour who did not agree with him, including Gordon Brown and much of recent-ish Labour Party history. And note the contrast with Blair’s understanding of the Pauline moment:

We had become separated from ‘normal’ people. For several decades, even before the eighteen years in the wilderness, Labour was more like a cult than a party. If you were to progress in it, you had to speak the language and press the right buttons…The curse of Gordon was to make these people co-conspirators, not free-range thinkers. He and Ed Balls and others were like I had been back in the 1980s, until slowly the scales fell from my eyes and I realised it was more like a cult than a kirk. (Tony Blair, A Journey [London: Hutchinson, 2010], pp. 89, 641)

Not unlike Blair’s claims about the Labour Party and the Brownites, Lynch claims that like ‘any committed Evangelical group’ the Corbynite followers have shown no interest in whether connections with the wider electorate were being made.’ This may well have been true for those observed by Lynch but Lynch moves on immediately on with the claim that ‘the movement forming around him [Corbyn] is, at its heart, a form of political puritanism’, even if there are individual supporters of Corbyn who remain courteous and thoughtful. This construction needs some qualification. An argument can be made (indeed has been) that one of the main reasons that Corbyn and his immediate circle are pushing for control of the Labour Party is to create access to power for a wider extra-Parliamentary social movement and challenge the neoliberal settlement of the past forty years which is not happening with any of the mainstream political parties. Conceding power back to the majority of the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) will prevent this challenge, so that argument goes. But labelling the group as ‘puritanical’ obscures any differences of opinion and I know that there are MPs loyal to Corbyn who do believe they are reaching out to the public and have disagreed with him to his face over the years (which is presumably to be expected). You can agree or disagree with the main argument of Corbyn’s circle but the labelling of a group as ‘evangelical’ or ‘puritan’ obscures the group’s political reasoning and internal disagreements with a collective label of deviancy. Again, if we wanted to retain such labelling, could we not reverse it and suggest with Ralph Miliband (slightly modified) that New Labour or the majority of the PLP are more puritanical about the parliamentary system than socialism? Would the majority of the PLP be open to the views of anarcho-syndicalism? American libertarianism? Authoritarian capitalism? Presumably not. You may or may not think that is a good thing but to use the reverse labelling of the majority of the PLP as ‘puritanical’ in their commitment to maintaining the boundaries of their political views would also obscure their political reasoning and individual interests in the interests of promoting another.

Media

What is also striking about Lynch’s construction is his notion of the media in relation to political positions. Those mentioned by Lynch as supportive of Corbyn have faced ‘[y]ears of alienation from mainstream party politics’ and have resented ‘the sharp edge of right-wing media’. According to Lynch, they see Corbyn in an ‘honourable struggle against a hostile right-wing Party and media’ but criticises them by noting that ‘the fact that unhappiness against him stretches deep into the Soft Left and that Corbyn is now facing sustained criticism from the Daily Mirror.’ This is certainly one way to construct the political leanings of the English-based media where only a few organisations such as the Mirror, Guardian and Independent would ordinarily be classified as liberal or left-leaning.

Momentum, according to some imaginations (this very image has been used of them)

But another way of classifying the media (following e.g. Noam Chomsky, David Edwards and David Cromwell) might be one which, for all the differences of opinion, reflects dominant socio-economic concerns of owners and interested parties and its most representative political perspectives might stretch from (say) the UKIP Right to the Soft Left of the Labour Party, with a few dissenting voices at its constructed extremes. If we were to use this construction of the English-based media then the views of Corbyn are to be located at the fringe of dissenting voices from the outset (and were often pushed well beyond). Indeed, this seems to be reflected in some of the evidence collected and studied over the past year, from the twenty-plus negative Guardian articles in one week in July 2015 when it was clear Corbyn might win to the most recent analysis of the reporting of Corbyn since September 2015. Put another way, is it not entirely predictable that Corbyn was going to be opposed from across the mainstream media right from the outset? Put yet another way, does not this construction of acceptable opinion and acceptable disagreement function as ‘sectarian’ or ‘puritanical’ boundary marking its own right, ‘deeply convinced of the truth of their way of seeing the world’? But what is clearly at stake, whatever we make of such labelling, is what can be classified as the acceptable ideological limits of mainstream English political discourse.

Englishness

There is a nationalistic element to this construction of Puritanism which is focussed on assumptions of Englishness, or at least a significant aspect of Englishness. Lynch argues that it is inevitable that the ‘Corbynist movement’ will eventually find new ‘traitors’ to blame for their ‘inevitable’ electoral failures and the flipside of this is that there is ‘a deep current in English cultural life that is antipathetic to puritan movements’ which Lynch endorses. Indeed, he argues that we should ‘trust those deep pragmatic sentiments in our national life’ and (note the language) ‘believe’ that an isolated Corbynist ‘will be banished to electoral obscurity’. By way of an alternative, he argues, following the logic of the construction of a certain parliamentary centrism, we should ‘take on the deeper challenge of ensuring that the one nation aspirations that Theresa May sought to lay claim to yesterday are genuinely realised as we enter this crucial period of national reconstruction.’

The non-Puritan Corbyn

I do not know if there is a deep English antipathy to puritan movements or if this should be elevated to the level that it can help predict electoral results. It remains to be seen if there is a sufficiently widespread electoral perception of the Corbyn movement as both ‘puritanical’ and (thus) ‘unelectable’ in relation to Englishness. This would need a substantial study. However, whatever the analytical validity of such claims, they are part of competing discourses about Englishness or Britishness in relation to the language of religion. By way of contrast to Lynch’s construction of Englishness, there is a repetitive tradition of constructing a specifically English and specifically radical socialism, which is typically understood to run from the Bible through the Peasants’ revolt, the Diggers and Levellers, the Chartists, and the Trade Union movement, through various figures on the Left of Labour’s history and has been utilised by Tony Benn and, in a different way, by Corbyn.  Orwell himself (who is now surely one of the main sources of English political authority, irrespective of what he might have written) was a fan of this tradition and last summer it started to become associated with Corbyn. I am not necessarily suggesting that we do, but could we not alternatively claim that there is a ‘deep current in English cultural life’ which invokes this tradition and makes its own claims on an English heritage, and that we should rather try to realise its aspirations in this crucial period of national reconstruction?

Orwell himself (who is now surely one of the main sources of English political authority, irrespective of what he might have written) was a fan of this tradition and last summer it started to become associated with Corbyn. I am not necessarily suggesting that we do, but could we not alternatively claim that there is a ‘deep current in English cultural life’ which invokes this tradition and makes its own claims on an English heritage, and that we should rather try to realise its aspirations in this crucial period of national reconstruction?

If that is too much, we—or rather I—can at least rejoice in there being more and more data using the language associated with religion to construct and police boundaries in English political discourse.

I had to listen to the Peel Session version with the line ‘the conventional is now experimental … the experimental is now conventional’ added which holds true more than ever. How old was he then?

It seems to me that we all have fallen for that one with liberalism uber alles … ‘Oh we are so nice to the LGBT community and free speech is intrinsically good but we will continue to shaft all of you regardless of gender, sexuality or political sympathies with misery upon misery.’

The only coherent Christian response to the exceptional way in which we are ruled at the moment, not to say that I agree with it entirely, is Eastern Orthodox as far as I can see.

As far as a British response goes, well let’s just say that there isn’t a ‘hip-priest’ in sight although Giles Fraser is perhaps trying his best.

Would it be going too far to say that ‘I am Kurious Orange’ was the greatest work of British political theology of the last century?

What is your opinion on the Radical Orthodoxy crew?

On the subject of Corbyn I believe that in his heart he wanted to leave the EU and the only reason the he did not argue a positive case for Brexit was to pander to the PLP and their misplaced preconceptions about where the electorate were at.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Congrats on The Fall references! They are always welcome here.

Agree on liberalism.

I don’t know if there is or is not a coherent Christian response (at least one that stands alone as distinctively Christian) but I’d again mention those those radical traditions which dovetail with various parts of the radical left more generally. I have to say that Fraser has been pretty interesting in all this. It seems the Left of the Guardian (e.g. Owen Jones, Zoe Williams) who might have had or still have Corbyn sympathies are conceding more ground in the past days/weeks but he’s still holding on and emphatically, it seems. As for Kurious Oranj, top 3 surely! Also kurious about your view on Eastern Orthodoxy: can you elaborate?

I can’t say Radical Orthodoxy is my thing for various reasons e.g. the idea of virtuous and justified elites, closeness to the Tories (in some strands), ahistorical romantic nostalgia etc.

I wouldn’t be surprised if you are right about Corbyn. He had been arguing it for years and Brexit was, of course, the very vocal opinion of his mentor a Christian radical, Tony Benn.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And I see you are blogging!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is probably more accurate to say I have blogged … one article and a few quotes as I recall but I have an old piece about how the Anglican Church should crucify itself that I was thinking of putting on there.

I follow a few blogs on here, The Soul of the East, Jay’s Analysis and The Fourth Revolutionary War (sympathetic to the ideas of Alexander Dugin) that give a perhaps idiosyncratic account of the Orthodox position. It is an interesting response to liberalism but I have some reservations about it. However I am really not sure if that is because of social conditioning!?

I’m with you on Radical Orthodoxy … a very diplomatic answer. I like MacIntyre very much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Talmidimblogging.

LikeLike

You, Sir, are the great Antinomian of contemporary English religio-political commentators.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for thanking the time out of your busy schedule but given your history with antinomianism you’ve got me worried

LikeLike